DC adult learners may qualify for regular diplomas—whatever those mean

DC education officials are planning to grant high school diplomas to adults who complete high school equivalency programs. But some members of the State Board of Education have challenged one program's rigor, raising the question: What does a DC high school diploma actually signify?

Adults in DC who pass the GED exam currently receive a certificate, not a high school diploma. Some employers and colleges prefer a diploma.

In 2014, the GED organization overhauled the test, aligning it to the Common Core educational standards. The computer-based exam is now seven hours long and calibrated so that 40% of traditional high school graduates wouldn't be able to pass it.

In recognition of that increased rigor, DC's State Board of Education (SBOE) recently directed the State Superintendent of Education to draft regulations that would award high school diplomas to GED graduates. But in a more controversial move, the regulations would also confer state diplomas on those who graduate from the lesser-known National External Diploma Program (NEDP).

Rather than taking a single test, NEDP graduates must demonstrate 70 different "competencies" in subjects like financial literacy, civic literacy, history, and science. Students work one-on-one with a "buddy" and then are assessed individually on each competency.

The NEDP works better for some adults, but its rigor is unclear

Adult educators say the NEDP, intended for students 25 and older, is better than the GED for people who suffer from test anxiety or have unpredictable work schedules that prevent them from attending regular classes. There are NEDP programs in seven states in addition to DC, which has eight NEDP sites.

The developers of the NEDP say the assessment, like the GED, has been revamped to be more rigorous. And administrators at Academy of Hope, a DC adult charter school that offers both the GED and the NEDP, agree. Five of the six students who got the NEDP credential at the Academy last year are now enrolled in college and are doing well, they say.

But Ward 3 SBOE member Ruth Wattenberg and two of her colleagues have asked for objective evidence of the NEDP's rigor, along the lines of the documentation provided for the GED. The NEDP specifies standards and tasks— In response to Wattenberg's questions, the State Superintendent of Education, Hanseul Kang, has promised that testing experts at her agency will conduct an independent evaluation of the NEDP's rigor before the SBOE votes on the regulations at its meeting on January 20th.

One wrinkle is that graduates of the NEDP program already get regular diplomas, albeit ones issued by individual high schools rather than by the State Superintendent. At Academy of Hope, for example, NEDP graduates get diplomas from Ballou STAY, an alternative DC Public School high school that is also an NEDP site.

Kang says her office included the NEDP in the proposed regulations to ensure that in the future, graduates get a diploma regardless of where they complete the program. But the fact is, the proposed regulations wouldn't change the current situation for NEDP graduates.

Still, Wattenberg says that including the NEDP in the regulations without evidence of the test's rigor would set a dangerous precedent and— What level of rigor does a regular diploma require?

That may be true. But a larger problem is that we don't know the level of rigor required to obtain a regular DC high school diploma.

Yes, DC's graduation requirements, which are Common Core-aligned and include three years of math, look rigorous on paper. And it's true students have to pass their courses in order to graduate.

But those familiar with high-poverty high schools say students are often promoted from grade to grade without having mastered course content. Teachers may be under pressure to keep up a school's graduation rate, or they may not want students with behavior problems back in their classrooms for another year.

And some high-poverty high schools saw none of their students score proficient in reading or math on Common Core-aligned tests given last year. On last year's SAT, eight DCPS high schools had average scores below 1,000, well below the national average of 1490.

Current graduation requirements are unrealistically high

A more fundamental question is whether we've set high school graduation requirements— Over 60,000 DC residents 18 or older lack a high school diploma or its equivalent. Many need diplomas to enter apprenticeship programs in the construction trades, or to move up in fields like health care or day care.

But officials at Academy of Hope say 90% of their students arrive functioning at or below a 6th-grade level. And it takes 400 hours to prepare them for the new GED, as compared to 100 for the old one. The numbers taking the tests have dropped significantly because of the new rigor, they say.

The biggest obstacle is algebra, as it is for students at traditional high schools. But according to one estimate, only 5% of entry-level workers actually need to be proficient in algebra. Are we simply putting an artificial barrier between people who could handle the demands of many jobs and employers who would like to hire them?

We should require that a high school diploma signifies a certain level of achievement, as Wattenberg argues. But ideally, that requirement would apply not just to adult learners but also to the many more who obtain diplomas the usual way.

And we need to question the assumption that high school or its equivalent is just a stepping-stone to college, especially when so few DC high school students get there. True, a high school diploma alone doesn't mean much in the job market these days. But that could change if we started equipping high school students with skills that would actually render them valuable to employers.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

DC schools are missing an opportunity to equip students for coding jobs

In recent years schools in the District have expanded opportunities for students to learn computer coding, an occupation where demand is outpacing supply. But they could do much more to engage low-income students in a potentially lucrative career path that doesn't necessarily require a college degree.

There's been a lot of talk lately about the importance of teaching computer science in K-12 schools. Last week was Computer Science Education Week, during which students in DC and around the world participated in online tutorials billed as an Hour of Code. As part of the fanfare, the incoming Education Secretary, John King, visited a classroom at DC's McKinley Tech High School.

DC and 26 states now allow computer science courses to count towards graduation requirements, up from only 12 states two years ago. At least two DC charter high schools offer coding classes, and DC Public Schools offer a wide range of computer-related courses and extracurricular activities, although it's not clear how many students take advantage of them.

But much of the effort in DC and elsewhere is aimed at getting students to enroll in college and major in computer science. King, for example, asked how many of the two dozen students he addressed at McKinley wanted to study computer science in college. He was pleased when over half raised their hands.

There's nothing wrong with students majoring in computer science in college, of course. In fact, it's an excellent idea. The median salary for computer programmers is over $76,000. There are currently over half a million open computing jobs, according to Code.org, and last year fewer than 40,000 people graduated with computer science degrees. Forecasters predict that mismatch between demand and supply will continue at least through 2020.

The shortage of qualified college graduates is already creating pressure on employers to hire people who can simply do the work, whether or not they have the credentials. At Google, for example, 14% of the members of some teams have no college education. In general, 38% of those working as web developers aren't college graduates.

Some coders and programmers are self-trained, while others have gone through coding "boot camps" that give participants the skills they need in a matter of months. Although Obama administration officials are intent on encouraging students to go to college, they've also launched an effort to enroll more "low-skilled" individuals in coding boot camps and match them with employers.

Why not teach coding skills before kids graduate from high school?

No doubt these programs can be lifesavers for many who don't have the interest or resources to acquire a college degree. But why wait until after they've graduated from high school? Why not give students in K-12 schools the opportunity to acquire the skills they need to snag a well-paying coding job if they want one?

That's the theory behind the efforts of one DC nonprofit to bring coding classes to low-income kids beginning in 5th grade. The Economic Growth DC Foundation is in its second year of sponsoring its Code4Life program, which runs free weekly classes at one DCPS and two charter schools. The idea is that students will remain in the afterschool program through high school, receiving a series of digital badges that will ultimately render them employable as coders.

On a recent afternoon at KIPP DC Northeast Academy, kids in the program weren't focused on their future career prospects. But they were engaged and having fun. In one classroom, a half-dozen 5th-graders were using a simple program called SNAP to create intricate moving designs on their laptops. Down the hall, a group of 6th- and 7th-graders were learning how to use Excel spreadsheets to manipulate data.

At the same time, the kids were breaking down operations into steps and making the computations necessary to write their programs, acquiring logical reasoning and math skills that will serve them well regardless of what they ultimately choose to do.

Code4Life currently serves a total of only 75 students and relies on volunteers from Accenture and other places, including area colleges, to put together its curriculum and teach classes. The foundation's chairman, Dave Oberting, says he'd like to expand the program to more schools, but that would require funding to hire paid staff.

Ideally, Oberting says, he'd like to see coding become a standard part of the curriculum throughout DC. Code4Life, he says, "is a mechanism for showing that [teaching coding] isn't that difficult."

In some places, coding class is mandatory for all

Other school systems are managing to do it. Earlier this year, Arkansas passed a law requiring all public and charter high schools to offer computer science classes. Some places are starting before high school— The Chicago, New York, and San Francisco school districts have pledged to start teaching computer science to students of all ages. A largely low-income and Hispanic elementary school district near Phoenix is requiring every student to take coding classes. And beginning this year, Great Britain is mandating computer science classes for all students from the age of five.

One problem impeding some of these efforts is the difficulty of hiring qualified teachers, because people with computer skills can generally find better-paying jobs. But teacher salaries are relatively high in DC, so that might not present as much of an obstacle here.

Considering the potential benefits, all schools in the District— Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Lower test scores aren't necessarily a sign we're heading in the wrong direction

This week Mayor Muriel Bowser and other DC officials released long-awaited results for grades 3 through 8 from the Common Core-aligned tests given last spring. As expected, scores were far lower than on the old tests, especially for low-income and minority students. But that doesn't necessarily mean DC schools are on the wrong track.

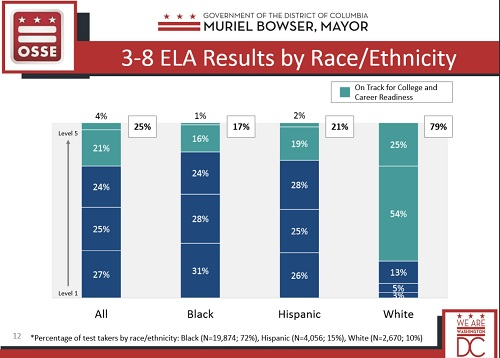

Proficiency rates on DC's old standardized reading and math tests hovered around 50%. On the new tests— But scores on the new tests aren't equally lower for all students. White students did far better than average on the PARCC tests, while minority and low-income students did worse. That was true on the old tests as well, but— Scores on the PARCC tests fall into five categories, with the highest two (4 and 5) considered to be meeting or exceeding expectations for "college and career readiness." As you can see from the chart below, far more white students fell into that category than black or Hispanic students. And far more black and Hispanic students than whites fell into the lowest category, "Did not yet meet expectations."

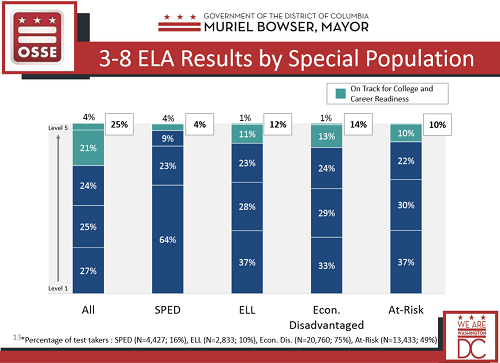

The gap is even larger between white students and other groups, such as students in special education (SPED) and English Language Learners (ELL). (The "at-risk" category includes students in foster care or receiving government benefits.)

On the old reading tests given in 2014, the gaps between whites on the one hand and blacks and low-income students on the other were about ten percentage points smaller than on the PARCC. The gap between white and Hispanic students was about 15 points smaller, while the gap for SPED students was only one point smaller.

If you want to explore the PARCC data in detail, there are various spreadsheets and other resources available on this DC government website, and a series of nifty interactive graphics are on the District, Measured blog.

The PARCC reading tests assume more knowledge

Why have the gaps grown? The unsurprising answer is that the tests have gotten harder. And, as various officials explained at the rather sober press conference called to unveil the new scores, that's something that needed to happen. The old tests were so easy they didn't mean much. As in other cities, students in DC— And what makes these new tests harder? I'm not that familiar with the Common Core math tests, although I know they require students to demonstrate they understand math concepts rather than just apply math rules. On the reading side, though, the basic reason is that the reading passages on the test assume that students know more vocabulary and are familiar with a wider range of concepts.

Standardized reading tests, by their nature, don't test any particular body of knowledge. Instead, the tests assess a student's general ability to understand whatever is put in front of her. That's partly because different schools are teaching different content. And of course, it's important for students to develop general reading ability in order to function well in school and in life.

But, as cognitive scientists have shown, the ability to understand a given text depends a lot on whether you're already familiar with the words and concepts it contains. That may make intuitive sense: just think of what it's like to try to read a passage on, say, cellular biology if you know nothing about the subject. What's harder for some of us to grasp is how many words and concepts minority and low-income children aren't familiar with.

PARCC and the other Common Core testing consortium, SBAC, have released sample questions that provide an idea of the kind of knowledge and vocabulary the tests assume children will have. According to a group called Student Achievement Partners, the 3rd-grade questions use words like fraying, spouting, blossom, nifty, scorched, and nutrients. They also present topics and concepts like Babe Ruth, Indonesia, and the U.S. Congress, along with biological terms like gills, larva, and pupa.

More affluent 3rd-graders may not know all these terms, but— Schools can help close the knowledge gap

Some have concluded that, since so much of literacy is dependent on family background, there's not much schools can do about this situation. And schooling can actually make it worse: some studies indicate that the achievement gap grows the longer kids stay in school. But the fact is, we don't know what schools might be able to do to close the gap, because most elementary schools serving low-income kids haven't spent much time trying to systematically build their knowledge and vocabulary.

Instead, they've focused on the comprehension skills the tests seem to call for: finding the main idea, making inferences, and— "People want us to just flip a switch, and young people will be off to Harvard," DC Public Schools Chancellor Kaya Henderson said at Monday's press conference. "That's not the way it works."

She's right: these things take time. The real question is whether schools in DC are on the right track. Henderson and others point to data in the test results to argue that the answer is yes: generally higher test scores at the lower grade levels than in high school. That shows, they say, that kids exposed to the Common Core approach from an early age are getting it, and that they'll continue to do better when they reach high school.

But the tests get harder in high school, and kids may just hit a wall— Still, some DC schools are on the right track. A number of educators in DC, in both the charter and traditional public school sectors, have grasped the importance of building knowledge, especially for students who are disadvantaged. I've been in classrooms where kids are lapping up facts, words, and ideas that will serve them well in high school and beyond. Whether and when that knowledge shows up in their test scores should be a secondary consideration.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Are long waitlists for DC's public preschools hurting the entire school system?

At some DC Public Schools, the programs that prepare kids for kindergarten by teaching pre-literacy and math skills, like learning the alphabet and counting, are in such demand that many neighborhood residents are unable to enroll their children. If DCPS doesn't expand the number of preschool slots where demand is highest, it risks losing those families to charter and other non-DCPS schools.

A preschool classroom. Photo by Herald Post on Flickr.

Officially called the Early Childhood Education (ECE) program, it offers Preschool-3 (PS3) and Pre-Kindergarten-4 (PK4) classes at elementary schools around the city through a lottery called My School DC. When it opens on December 14th, thousands of families from around the city will enter in hopes of securing a seat at the school of their choice.

To apply, families fill out a single online application for participating public charter schools (PS3 through 12) DCPS out-of-boundary schools (K-12), most DCPS ECE (PS3 and PK4) programs including programs at in-boundary schools, and DCPS citywide selective high schools (9-12).

Each student may apply to as many as 12 schools per application. The My School DC lottery is designed to match students with the schools they want most, and maximize the number of students who are matched.

As 3 and 4 year olds are not required by law to attend school, DCPS is not required to offer a seat for every in-bound child. Therefore a child must enter the lottery to secure an ECE seat. DCPS is current piloting program that offers guaranteed seats for in-bounds PS3 and PK4 student at six Title I (low income) elementary schools across the city (Amidon-Bowen Elementary, Bunker Hill Elementary, Burroughs Elementary, Martin Luther King, Jr. Elementary, Stanton Elementary, and Van Ness Elementary) but families are required apply through the lottery to exercise this right.

Preferences are given to students that are in-bounds and have a sibling that attends the school, in-bounds students without a sibling at the school, and students that are out-of-bound and have a sibling that attends the school, in that order. A majority of elementary schools are able to offer seats to all of their in-bounds ECE students. If there is a waitlist, students are ordered by the lottery based on the algorithm, which accounts for any preferences a student may have.

The in-bounds waitlists can be very long

The list of schools that are able to accept all of their in-bounds students into their ECE programs is shrinking. Last year 25 schools had to waitlist one or more of their in-bounds ECE students. The schools on this list put an average of 25% of their in-bounds students on the waitlist, although in some cases it was much higher.

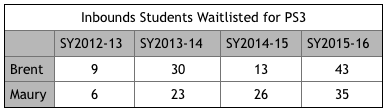

Of the four schools that waitlisted 50% or more of their in-bounds students, two were located in Ward 3 (Stoddert and Oyster-Adams) and offered only PK4 slots, while the others were located in Ward 6 (Brent and Maury) and offered positions for both PS3 and PK4 students.

Brent and Maury provide examples of how quickly things can change:

These numbers offer a poor introduction to many families that DCPS is trying to attract and retain. The situation is worse for new families, as children with older siblings in the school receive priority over other in-bounds students. This past year, in-bounds students without siblings had a 24% chance of getting into Maury's PS3 class and no chance of getting into Brent as they had 39 students receiving the in-bounds with sibling preference for only 30 PS3 spots. While there is a chance that students could receive a PK4 seat the following year, the fact remains that a large percentage of in-bounds families will not experience the best recruiting tool DCPS has to offer.

Families are deciding about middle school when their kids are three years old

At a time when DCPS is taking steps to encourage families to stay beyond elementary school, potential new families can see these large waitlists as a deterrent. DCPS also risks losing these students to private schools, DC public charters, or other districts with more established middle school options.

Even if the student returns for kindergarten, DCPS has missed an opportunity to build loyalty with these students and their families, which matters in neighborhoods with unsettled middle school situations like Capitol Hill. Due to the increasing number of middle school options, some families are choosing to leave DCPS elementary schools as early as second grade.

Also, the charter middle schools that are popular with Capitol Hill families such as BASIS and Washington Latin start in fifth grade, which also pushes up the Middle School Decision timeline. As a result, DCPS may only have a few years with a student that starts in kindergarten to demonstrate they are a viable option beyond fourth grade.

Here's what DCPS can do about this problem

One option is for DCPS to eliminate PS3 classes in the schools with long in-bounds waitlists and convert those seats into PK4 seats. This still may not provide room for all in-bounds students, but by bringing in a larger percentage of the in-bounds population for one year it would offer a better experience for more families and would reduce the "Golden Ticket" feeling that divides communities into haves and have-nots at three years old.

It is notable that in Northwest DC, only two of the twelve elementary schools that flow to Wilson High School offer PS3 classes. While many of those twelve schools still have to waitlist in-bounds students applying for PK4 seats, in several cases they are able to accommodate a much larger percentage of their in-bounds students. As DCPS tries to create a "Deal and Wilson for all," Eastern High School and the schools that flow to it offer DCPS a chance to re-create that model, which starts for most families at PK4.

As more families choose to stay in the city, it is likely that DCPS will have additional schools that experience large increases in the number of in-bound applicants from one year to the next. However better demographic information in the school districts would allow DCPS to predict and then plan for these large increases in order to minimize the waitlists.

As DC changes, its preschool programs will need to as well

The DCPS ECE program is a great resource for District families, and is often the envy of our friends in Maryland and Virginia. While it is often derided as "free day care," ask parents with children in one of the classes around the city and instead they will talk about the excitement of their students describing metamorphosis and reading and writing their first words. They will also talk about the relationships their children have developed with the other students and the sense of community a neighborhood school can provide.

As DC continues to change, DCPS must be able to anticipate these changes and adapt as well. Investing in information gathering will benefit DCPS by allowing neighborhood schools to better predict how large rising classes of in-bounds three year olds may be.

DCPS has made significant strides convincing DC families that the DCPS elementary schools will provide an excellent education for their children. In fact, they have been so successful that families are clamoring for seats in their ECE programs. However, the next phase, persuading DC families to believe in DCPS middle schools, begins with families' first interactions with DCPS.

DCPS has the ability to make that interaction better.

Correction: An earlier version of this post stated that families who wanted to claim an in-bounds state at one of the six schools that guarantees admission to their ECE program did not need to go through the My School DC lottery. That's incorrect. Students must still apply through the lottery to claim their in-bounds seat.

DCPS schools put unmotivated students in AP classes. That doesn't work.

An influential education columnist is applauding the DC Public School system's decision to expand Advanced Placement offerings, arguing that any motivated student should be allowed to take the college-level courses. But many high-poverty schools in DC simply assign students to AP classes even if they're not willing to do the work.

In September I wrote a post questioning DCPS's decision to require all high schools to offer at least six AP courses this year and eight next year, an increase over the previous minimum of four.

I pointed out that at DC's high-poverty neighborhood high schools— Washington Post columnist Jay Mathews, a longtime proponent of AP expansion, has now responded to my post by arguing, as he has in the past, that students benefit from AP classes regardless of whether they pass the test.

Mathews' views are important. He publishes an annual ranking of high schools across the country, based on the number of AP tests given at a school, that has largely fueled the recent rapid expansion of AP courses across the country.

Mathews and I agree that any student willing to work hard should be able to take an AP course or something like it. But Mathews believes the problem is that schools are keeping motivated students out of AP classes because they don't have top grades or haven't met certain prerequisites. That was the case when Mathews first started writing about AP classes 30 years ago, and he says it's still true in many schools today.

But that's not the problem in DC. Instead, most high-poverty high schools here appear to be putting students into AP classes who haven't chosen to be there. Those students aren't getting anything out of the courses because they're unwilling to do the necessary work. And the motivated students often don't get the support they need because the size of the class is too large to allow that to happen.

Most AP teachers don't have the leverage to exclude unmotivated students

After Mathews expressed interest in writing something about my post, I put him in touch with David Tansey, who teaches AP Statistics at Dunbar High School, a high-poverty DCPS school. In 2013, 94% of the AP exams given at Dunbar received a score of 1.

In his column, Mathews focused on Tansey's ability to limit his class to motivated students, using that example to bolster his arguments for AP expansion. When Tansey decided last year that he would teach an AP class for the first time, he recruited selected students, told them this year's course would require hard work, and gave them a letter their parents needed to sign before they could enroll.

But Mathews overlooked the fact that what Tansey did was highly unusual. Tansey is in his seventh year at Dunbar, which makes him one of the most senior teachers there, and he consistently gets high ratings under DCPS's teacher evaluation system. The vast majority of AP teachers in schools like Dunbar don't have the leverage to convince school administrators to limit their classes to motivated students, he told me.

Instead, Tansey said, administrators simply tell some students, "You're taking AP," whether the students want to or not. Perhaps it's the only class that fits with a student's schedule, or the other possible options are too crowded. And administrators may assume students who make As or Bs at their schools can handle AP-level work.

But that's not the case. An AP course is supposed to cover a year of college-level work. But even high-achieving students at a school like Dunbar may be behind grade level, so they might have to first cover a year's worth of high-school-level material before tackling AP material— Even motivated students at high-poverty schools often need intensive support to do AP-level work, ideally in small classes. But at the same time that DCPS has told high-poverty schools to expand AP offerings, it hasn't given them money to hire more teachers. So schools are under more pressure than ever to increase the size of AP classes, to prevent other classes from getting too big.

Teachers can and do "dumb down" AP classes

The crux of Mathews' pro-AP argument is that teachers can't dumb down AP classes because "outside experts," not the teachers themselves, grade the final exams. Although he acknowledges in his column that "a few AP teachers" commit "malpractice" by going easy on kids, he assumes the vast majority grade quizzes and essays on the same tough scale the outside experts will apply on the final AP exam.

But Tansey says that what Mathews assumes is a rare occurrence is actually common practice in high-poverty schools. Kids at schools like Dunbar, he says, have been "battered by failure." If you apply AP-level standards to quizzes and give students Fs, they may just stop trying. And even students' grades on the final AP exam, he says, aren't that important to them because they arrive after the course is over.

Still, Tansey says that with a couple of exceptions, the 21 students in his AP class this year are working hard and getting more out of the experience than they would in a regular math class. So, even though he's just now beginning to introduce AP-level material, Tansey's experience seems to support at least part of Mathews' hypothesis: motivated students will benefit from a more rigorous class.

But that doesn't mean it has to be an AP class. As Tansey said in an email to Mathews that I was copied on, "'Offer more APs!' is the wrong call. 'Offer challenging courses, like AP courses, that students have to choose to accept the rigor of' is a better call."

That's a comment Mathews chose to ignore— But DCPS officials, at least, should pause and consider whether simply mandating more AP courses in high-poverty schools, without providing funds for additional teachers, will actually benefit students. As Tansey suggests, a more sensible goal would be to match all students with classes they actually want to be in— Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Test scores may rise or fall, but the achievement gap persists

On Tuesday, officials released dismal scores from the new Common Core-aligned tests students in the District took last spring. The next day, another set of scores showed DC students improving faster than those in the rest of the country. One thing that was consistent in the results was a large gap between rich and poor.

The first set of scores, on standardized tests known as PARCC, showed that only 25% of DC high school students were "college and career ready" in English. Even worse, only 10% met that bar on a test of high school geometry.

That looks like a huge drop from scores on the old DC test, known as the DC CAS. Last year, about 50% of 10th graders scored proficient or advanced on those reading and math tests. (PARCC scores for 3rd through 8th graders won't be available until next month. They may be somewhat better than the high school scores, but will probably also decline significantly.)

You might conclude that students' skills have suddenly plummeted, but in fact the two tests aren't comparable. The PARCC tests, which are designed to measure whether students have the skills they'll need to succeed in college, are far more rigorous. Instead of asking students to write an essay about their dream vacation, for example, a test might give them two sophisticated passages to read and ask them to make detailed comparisons.

In past years, DC's education leaders and elected officials have celebrated incremental progress on the DC CAS. This year, they lamented the low PARCC scores and somberly declared they were prepared to do the hard but necessary work to improve them. But barely had the words left their mouths, or their press releases, when their lamentations turned to joy.

DC's growth in NAEP scores outpaces the rest of the country

That's because DC bucked a national trend on the other test: the NAEP, given to a sample of students across the country every two years. The NAEP is considered far more rigorous than most of the old state tests, including the DC CAS. This year, math scores for 4th and 8th graders declined nationwide. But in DC, 4th grade scores rose by three points in math and seven in reading, while 8th grade scores remained flat.

On the face of it, the PARCC and NAEP results appear contradictory. But the tests were differently constructed, and they were assessing different grade levels. And while it's true DC's NAEP scores have gone up, they're still at or near the bottom compared to other states.

But of course, DC is more like a city than a state. And cities, which have higher concentrations of poverty, tend to have lower test scores. So it's fairer to assess DC's performance against another set of NAEP scores that compares large urban school districts to one another— On that measure, DCPS has improved— Both sets of scores reveal gaps between subgroups

One thing that the NAEP and PARCC scores have in common is that they reveal the width and persistence of DC's achievement gap. On the PARCC test, for example, School Without Walls— Some previously high-performing charter schools saw their scores drop precipitously, as has happened elsewhere. Last year at KIPP DC College Prep, where most students are black and low-income, 95% of students scored proficient in math and 71% in reading on the DC CAS. This year, just under 20% of students met the PARCC bar in either subject.

Gaps between ethnic and socioeconomic groups loomed wide on the DC CAS, but PARCC has turned them into chasms. On the PARCC English test, for example, 82% of white students met "college and career ready" expectations, compared to 20% of black students, 25% of Hispanics, and 17% of economically disadvantaged students. On last year's DC CAS in reading, an even higher percentage of whites scored proficient— And despite the increases on the NAEP for DC as a whole, a demographic breakdown of DCPS's scores reveals that gaps seen in previous years haven't budged. In 8th grade reading, for example, 75% of white students scored proficient as compared to 11% of black students, 17% of Hispanics, and 8% of low-income students. In DC as a whole, the gaps between white students on the one hand and black and Hispanic students on the other are the largest in the nation on the NAEP, according to one calculation.

To be fair, one reason for the size of the gaps is that DC's white and affluent students perform at an unusually high level. But to begin to close that gap, disadvantaged students need to improve faster than white ones. In fact, looking just at DCPS scores, proficiency rates for white students have either gone up or stayed the same on each of the four tests since 2013, while at least one other subgroup's rate has gone down on all but one of the tests.

On the English and reading side, the root cause of the gap in scores is the relative lack of exposure low-income students have to knowledge and vocabulary, starting from birth— Some will see the test scores, and the gaps they reveal, as evidence that education reform hasn't worked. Critics of the Common Core standards may use the PARCC results to argue the tests are unrealistically hard. Those on the other side will say the Common Core is revealing deficiencies that were masked by the DC CAS, and point out that this kind of change takes time.

There's some truth to all those arguments. But the bottom line is that our schools are continuing to fail many students who enter with the greatest deficits, and we need to find a way to bring their knowledge and vocabulary closer to the level of their affluent peers. Test scores can tell us how far we still have to go, but they won't tell us how to get there.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

For Alexandria and Arlington elections: Bill Euille, Katie Cristol, Christian Dorsey

Many residents of Arlington and Alexandria watched Wednesday night's GOP presidential debate, but there's an election coming up much sooner which will have a major impact on life in those Northern Virginia localities.

Virginia voters go to the polls Tuesday to elect representatives in local county or city offices and state legislature. In the local races in Arlington and Alexandria, Greater Greater Washington endorses Katie Cristol and Christian Dorsey for Arlington County Board and recommends writing in Bill Euille for mayor of Alexandria.

Left to right: Bill Euille, Katie Cristol, Christian Dorsey. Images from the candidate websites.

Arlington County Board

In Arlington, incumbents Mary Hynes and Walter Tejada both decided not to run for their seats on the five-member board this year, shortly after the other three members voted to cancel the Columbia Pike streetcar.

Democratic nominee Katie Cristol stands out as the strongest on urbanism. In Friday's debate, she expressed strong support for a better transit network, protected bikeways, and allowing the county to grow.

Christian Dorsey, the other Democratic nominee, is clearly a step behind Cristol on transportation and growth but far ahead of the other two. (Voters will vote for two candidates for two seats.) He supports better transit, but is nervous about transit-oriented development without high parking requirements and doesn't yet understand the need for protected bicycle infrastructure.

Dorsey also has support from Libby Garvey and John Vihstadt, two members of the county board who won office largely by telling voters in the most affluent parts of the county that they shouldn't have to pay to build transportation and recreation infrastructure for anyone else. However, this doesn't mean he will take a similar approach, and he seems open to learning from his colleagues on the board and people in Arlington. He's also clearly superior to the other two options, Audrey Clement and Mike McMenamin.

Clement thinks Arlington has grown too much and doesn't want to build more bike trails. McMenamin doesn't want more density either because it could add to traffic (not realizing that Arlington has grown without making traffic worse), thinks adding more parking is more important than better transit, and would only consider bike infrastructure in the context of how it would affect drivers.

To make an endorsement, Greater Greater Washington polls our regular contributors and makes an endorsement when there is a clear consensus. Here's what some of our contributors had to say:

- Cristol is great on transit—

understanding the need for supporting non-work trips to really enable car-free and car-lite living. She has actual concrete suggestions on improving Columbia Pike bus service. She understands and talks about the economic benefits of cycling infrastructure and supports the expansion of protected bike lanes. She's the best candidate in the bunch. - [Cristol and Dorsey] have a firm commitment to affordable housing, without Audrey Clement's anti-intensification NIMBYism.

- Clement just doesn't know how cities work and many of her proposed policies are way too proscriptive and busy-bodyish. McNemamin is one of those who sees everything as waste but wants to widen 66 and make parking easier.

- I know Katie Cristol and she is a pleasure to work with. She seems to be the most in line with smart growth ideals than any of the candidates. Dorsey seems OK and better on the issues than the two other candidates, though his positions seem a bit more qualified.

In Alexandria, there is only one candidate for mayor on the ballot, but there's a hotly contested race nonetheless that will determine the city's path for years to come. Alison Silberberg narrowly won the Democratic primary by 321 votes over incumbent mayor Bill Euille, but only because Kerry Donley played the role of spoiler, competing for the same base of voters as Euille.

Now, Euille is running as a write-in candidate, hoping the large majority of Alexandrians who supported him or Donley (who has endorsed his write-in candidacy) will help him defeat Silberberg.

As mayor, Euille has generally supported a vision of a growing, active, urban Alexandria which welcomes people getting around on foot or by bicycle. Silberberg, meanwhile, is running hard as the anti-change candidate who will stop Alexandria's growth and design the city entirely around the automobile.

Here are our contributors:

- Bill Euille supports the development that Alexandria needs both in Old Town and at Potomac Yard. Silberberg represents a contingent who act as if Alexandria is "full" and unable to grow.

- Alexandria's forward progress on cycling and the Potomac Yard Metro station have both come during Euille's tenure.

- Euille understands how municipal budgets work. He is a big supporter of economic development and smart growth. He is leading the way for a Potomac Yard infill metro station, and has supported transit corridors and improved bicycle and pedestrian ways.

- Silberberg basically doesn't understand that you can't lower taxes and vote "no" on growth while still providing needed infrastructure, supporting the schools, helping the elderly, funding affordable housing, and preserving every brick more than 50 years old.

Alexandria council

There are six at-large councilmembers besides the mayor. Incumbents John Chapman, Tim Lovain, Del Pepper, Paul Smedberg, and Justin Wilson are running for re-election. There is also one open seat, the one Silberberg now holds.

The Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Committee sent a questionnaire to the candidates, and heard back from Chapman, Lovain, and Wilson, as well as Monique Miles and Townsend "Van" Van Fleet.

Even many of our contributors have not followed this race intensely, and so there were not enough votes to make an endorsement. However, of those who did, there was praise for the five incumbents, particularly Lovain and Wilson.

Here's what they said:

- Chapman: Good thinker, came out with small business initiatives, supports growth around Metro.

- Lovain: transportation expert; head of TPB next year. Supported streetcars and high capacity transit.

- Pepper: This vote is for experience more than anything. She knows how government works, and has her ear finely tuned to citizen "wants." She can craft a compromise if needed to help a project move forward.

- Smedberg: For good government, fiscal responsibility, economic development, and environmental stewardship.

- Wilson: The brain of the City Council. He knows the ins and outs of every budget line item; can talk for hours on transportation, schools, budgets; has all the facts at his fingertips.

- Lovain and Wilson are the strongest supporters of Complete Streets, transit-oriented development and Capital Bikeshare. Wilson is also quick to give realistic answers to questions raised by the public, and often gets heat for it because residents don't always like the answers. During recent "add/delete" budget sessions, Lovain has led the charge for funding Complete Streets.

- Wood and Van Fleet are basically disgruntled about the waterfront plan and don't have anything positive to offer.

Virginia has vote suppression laws that require voters to have a photo ID; if you don't have one, you can get a voter-only one on Election Day at the Arlington to Alexandria elections office on Election Day (or an earlier weekday).

DCPS is expanding AP classes, but at some schools everyone fails the test

As part of her Year of the High School initiative, DC Public Schools Chancellor Kaya Henderson is expanding Advanced Placement offerings at all DCPS high schools. But at most high-poverty DC high schools, few if any students earn passing grades on AP exams.

Starting this year, DCPS is raising the minimum number of AP courses each high school must offer from four to six. Next year, all high schools will be required to offer at least eight AP courses.

The expansion of AP in DC is part of a nationwide trend, fueled by the idea that all students benefit from taking the ostensibly rigorous, college-level classes regardless of how well prepared they are.

The Washington Post's Jay Mathews, a leading proponent of the AP-for-all theory, publishes an annual ranking of US high schools based largely on how many AP tests they administer per graduating student. Although Mathews' methodology and assumptions have drawn criticism, his ranking has spurred much of the AP growth.

Nationally, AP participation rates have more than doubled in the past decade, with 2.5 million students taking at least one AP exam in 2015. But as the number of AP test-takers has expanded to include many more low-income and minority students, the failure rate has grown even more rapidly.

AP exams are graded on a scale of 1 to 5, and the College Board, which administers the exam, considers 3 to be a passing score, enabling a student to earn college credit. (Many universities give credit only for scores of 4 or 5.)

Nationwide, about 60% of all test takers scored a 3 or better on at least one exam. But the pass rate for African-American students was just half the rate for white students.

In DCPS overall, the proportion of exams on which a student earned a 3 or above has gone up from 27% in 2010 to 33% in 2015. But those figures, provided by DCPS, don't reveal much about how students at each school are performing. Students at some schools may be taking several AP exams, doing well on all of them.

A DCPS spokesperson, Michelle Lerner, declined to release school-by-school pass rates, saying that some AP classes are small enough that individual students could be identified. But a retired DCPS teacher, Erich Martel, has calculated school-level scores on the basis of information he received from an internal DCPS source. The data lists scores for all AP tests taken at each DCPS high school in 2012 and 2013.

At some schools, almost all tests get a score of 1

In 2013, according to Martel, the overall pass rate for DCPS was just under 31%. But that rate drops to lower than 10% if you exclude relatively affluent Wilson High School in Ward 3 and three selective schools— At four high-poverty DCPS schools— Overall, almost 46% of tests taken by DCPS students got the lowest score possible, a 1. But again, if you exclude Wilson and the three selective schools, almost 70% got that score. At Spingarn, all 24 tests received a 1, and at Dunbar, 49 out of 52 did.

Mathews and other advocates of AP expansion argue that students benefit from the experience of taking AP classes and tests, even if they don't pass the tests. Some studies have supported that claim, while others have refuted it.

The most recent study concluded that merely taking an AP class, without also taking the test, had no effect on a student's score on the ACT college entrance exam. Those who took and failed the AP test scored a quarter to half a point higher on the ACT, which is roughly equivalent to the boost a student would get from test prep coaching. (Students who passed the AP test scored from one to four points higher on the ACT, depending on which AP class they took.)

About 95% of DCPS students who take AP classes also take the test, according to DCPS. But the lead author of the recent AP study believes that students benefit not from the three hours spent taking the test but from the studying they put in beforehand. So the real question may be: do the many DCPS students who get 1s on AP tests actually study for them?

No doubt some AP teachers out there could answer that better than I can. But when I volunteered as a tutor for a college-level history class at a high-poverty high school a couple of years ago, I realized that most students in the class lacked the background knowledge and vocabulary to gain even a basic understanding of the texts. And if students can't understand the material, they can't study for the test.

An AP score of 1 could mean that a student showed up for the test and just answered questions randomly, or didn't answer them at all. A study cited by Mathews in support of AP expansion shows benefits for students who get "even a score of 2" on the AP, but says nothing about those who get a 1.

AP-for-all defenders argue that even if students are unprepared for AP classes, they'll get more out of them than they would out of regular classes where exams are graded, not by an independent entity, but by teachers who may be willing to lower standards. But if the AP material is far above students' heads, they may not be getting anything out of the classes at all. Perhaps we need a third alternative: classes that are both rigorous and accessible to the students who are taking them.

While building a pipeline, keep AP classes small

"We believe that at every school there are students at AP level," says DCPS's Lerner. That may be true, but at high-poverty schools even those students probably need a good deal of support to do well. And unless classes are small, they won't get it.

Lerner says DCPS schools are required to offer the minimum number of AP classes even if only a few students enroll. But will school administrators resist the temptation to herd large numbers of students into classes they're not prepared for, as they seem to have done in the past?

Even if administrators keep AP classes small, without additional funds the result may be that other classes get larger. And the non-AP students may get inferior teachers, since schools generally assign their best teachers to AP classes.

Lerner says the district is "setting up a pipeline" for its AP classes and expects enrollment to grow in the future. That makes sense: if you want low-income students to be prepared for AP classes in high school, you need to start laying the foundation in kindergarten, if not before.

But increasing the number of AP classes now at all schools makes sense only if DCPS ensures the classes are limited to students who can actually get something out of them.

The original version of this post said that the scores compiled by Erich Martel were not broken down by AP subject. In fact, they include both aggregate AP scores for each school and subject scores. Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

How school choice can make it harder to solve the problems of poverty

For those who believe a system of school choice is the answer to our education woes, DC is a model for the rest of the nation. But the decline of the neighborhood school can make it harder to address the needs of poor children in a comprehensive way.

DC is a bastion of school choice, with only about a quarter of students attending their assigned neighborhood school. Overall, 44% of DC students are in charters, which draw from across the District, and many go to traditional public schools that are selective or located in neighborhoods other than their own.

Proponents of school choice argue that this kind of competition among schools leads to an improvement in school quality overall. But in some gentrifying DC neighborhoods, middle-class parents working to improve their neighborhood schools have long criticized a system that makes it relatively easy for parents to send their kids elsewhere.

"DC has created so many escape hatches— DC's Promise Neighborhood Initiative adopts a holistic approach

School choice can also make it difficult to improve children's chances of success in low-income neighborhoods, as illustrated by the experience of DC's Promise Neighborhood Initiative. Part of a nationwide program, the DCPNI has been receiving $25 million in federal grants to saturate an entire troubled area with social services and investments.

The initiative focuses on the Kenilworth-Parkside neighborhood in Northeast DC, where about half the residents live below the federal poverty line and nearly 90% of families with children are headed by a single female.

The area includes a charter middle and high school operated by the Cesar Chavez network and one DCPS elementary school, Neval Thomas. A highly regarded preschool program, Educare, has also located in the neighborhood. (There was a second elementary school in the area when the initiative began, but DCPS closed it shortly thereafter due to low enrollment.)

The idea behind Promise Neighborhoods is that just trying to improve the schools in a high-poverty area isn't enough, because the problems of poverty spill over into the classroom. DCPNI works with neighborhood families on a range of issues, teaching things like parenting skills and healthy eating practices and trying to build community engagement.

But the center of the model— That's not the case in Kenilworth-Parkside, where fewer than a third of the 1,600 students attend local schools. The rest are enrolled in a staggering 184 different schools around the District.

Schools in the neighborhood have gotten better. Neval Thomas now has an updated library and other amenities, and while test scores remain low, attendance has improved. And the Cesar Chavez campus earned high marks from the Public Charter School Board for the first time last year, with administrators crediting the tutors, new curriculum, and teacher training funded by federal Promise Neighborhood money.

But fewer than 100 of Cesar Chavez's 356 students came from Kenilworth-Parkside last year. And many neighborhood children aren't benefiting from the improvements at Neval Thomas because they attend school elsewhere.

DCPNI provides afterschool programs that are open to those kids, but it can be hard for them to get there on time if they're coming from schools in Northwest DC or if their schools have extended day programs.

The specifics of school choice may differ in gentrifying neighborhoods and low-income ones like Kenilworth-Parkside. But the end result in both cases is that many of the more motivated and engaged parents jump ship, ultimately leaving the neighborhood schools with a higher concentration of the most challenging students.

A neighborhood-based approach can make it easier to attack poverty-related ills

The children in Kenilworth-Parkside who go to school elsewhere may be getting a better education than those who remain, but they're not immune from the effects of poverty-related trauma. The schools they attend, whether charter or DCPS, usually aren't equipped to deal with the mental health issues they may bring with them, or to help their families acquire better parenting skills.

Some schools are trying to address these issues, but a community-based approach like DCPNI's would make it easier, especially when a school's families are far-flung. And a community-based approach stands a better chance of lifting the whole neighborhood, which may be the only way to lure some parents back to the neighborhood school.

"I don't want my kids going to school with neighborhood kids," one mother in Kenilworth-Parkside who sends some of her children to a charter told the Post. "People here have a lot of problems."

It's too late to dismantle the extensive system of school choice in DC, which has been expanded by the rise of charter schools but certainly existed before they came on the scene.

Lower-income families living east of the Anacostia River have long sent their children across town to more desirable DCPS schools. And higher-income families have always been able to exercise choice by moving to a neighborhood with better schools, either within the District or beyond its borders.

Restricting school choice at this point would be unfair to low-income parents who can't afford to move to a better school zone or district, and it could push middle-class families out to the suburbs.

But if we want to see improvements in all neighborhood schools— As many in the charter community have argued, a neighborhood preference wouldn't be appropriate for all charter schools, and it shouldn't be forced on them across the board. But if a charter in a low-income area wants to set aside some of its seats for nearby kids who want to attend, giving the school that option could provide some of the benefits of choice without undermining the institution of the neighborhood school.

And neighborhood preference could make it easier to address the poverty-related ills that prevent poor children from succeeding in school and in life, while also benefiting a whole community. Education reformers like to defend school choice on the ground that a child's chances of getting a good education shouldn't depend on her zip code. But in the era of No Child Left Behind, school choice has left many zip codes as far behind as they've ever been.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Some are questioning whether all students should be on a college prep track

A former professor who spent two years teaching in a high-poverty DC Public Schools high school advocates separating students into a college prep track and other tracks that would lead directly to jobs. But to really know who belongs in which track we need to revamp an elementary school system that has left almost all poor students woefully unprepared for a college prep curriculum.

The old practice of separating students into academic and vocational tracks has fallen into disfavor. That's because traditionally, school systems often funneled white and affluent students into college prep classes while relegating poor black ones into classes intended to prepare them for jobs in fields like auto repair and cosmetology.

Education reformers have generally insisted that all students follow a college prep curriculum. But some are beginning to recognize the value of what is now called career and technical education in engaging disaffected students and providing them with practical skills.

Some school districts, including DCPS, are beefing up their formerly anemic vocational offerings with new Career Academies embedded within neighborhood high schools. Two new ones, focusing on engineering and information technology, are opening this year at H.D. Woodson High School in Ward 7.

But these academies— A former teacher and others question whether "college for all" makes sense

Caleb Stewart Rossiter, a former professor at American University who spent two years teaching math at H.D. Woodson, proposes a different approach in his book Ain't Nobody Be Learnin' Nothin': The Fraud and the Fix for High-Poverty Schools..

Rossiter says only about 20% of students at schools like Woodson are "within striking distance of high school standards." And he argues that under the current system, those students will never be college-ready because they're being held back by students who are disruptive or hopelessly behind.

In some ways Rossiter's version of tracking differs from the paternalistic model that prevailed in the old days, when the school system decided which track a student should be on. Students and their parents or guardians themselves would choose either a college-prep or vocational track at 7th grade, with an option to reevaluate at 9th. Rossiter wouldn't exclude any students who are highly motivated from college prep.

But, as under the old system, Rossiter wants vocational tracks to lead students directly to jobs rather than to college. And he wants schools to require students who are years behind to undertake intensive remediation before embarking on either track, although they might need less remediation for the vocational one.

Rossiter's book details extreme dysfunction at Woodson (which he refers to as "Johnson" in his book), characterizing the "unspoken bargain of calm high-poverty classes" as "don't push me to work and I won't disrupt the class much." In addition to tracking, Rossiter wants extremely disruptive students and those far behind grade level removed from regular classes and getting counseling and non-credit remediation.

Rossiter isn't the only one questioning the assumption that all students should go to college. When students are in 11th or 12th grade and still reading and doing math at an elementary level, subjecting them to a grade-level college prep curriculum appears to be a waste of everyone's time.

And, as Rossiter argues, the supposed college-prep curriculum isn't even doing a good job with the low-income students who manage to make it to college: 64.5% of low-income students who enroll in a two-year college need remedial classes, as do 31.9% of those who enroll in a four-year college. Only 9% of the poorest students complete a college degree— True, poor and minority individuals who make it through college do far better than those who don't. But college doesn't seem to be the great equalizer that some had hoped for. A new study has found that black and Hispanic college graduates have far less wealth than their white counterparts.

So offering students the option of a track that leads to a job rather than to college makes sense. And there should be no shame in vocational education. Society needs beauticians and auto mechanics as much as it needs college professors and lawyers.

Vocational classes may solve some of the disciplinary problems afflicting high-poverty schools as well. As Rossiter saw when some of his most disruptive students eagerly embraced a challenging masonry task and excelled at it, some students are far more responsive and persevering when learning is part of a hands-on task.

Lately, some reformers— Before we embrace a version of tracking that allows some students to opt out of college prep, however, we should be aware of a couple of major caveats. One is that most decent jobs that don't require a college degree still require a high level of accomplishment. Some people who skip college and complete an occupational concentration in high school manage to out-earn college graduates, but only if they did well in Algebra II and advanced biology.

Inadequate elementary school education may be masking students' potential

More fundamentally, we may be overlooking a lot of undeveloped academic potential in low-income kids because of the education they get before they reach high school. Elementary education is currently so inadequate that we simply don't know how many kids would be capable of handling a college prep curriculum if they were given the right kind of foundation.

Even before standardized tests became important— Elementary schools have spent little or no time building students' knowledge of subjects like history and science. That's particularly harmful for poor kids, who are less likely to acquire that kind of knowledge at home.

When those kids get to high school, they suddenly encounter a curriculum that assumes a lot of knowledge and vocabulary they don't have. As a result, they can't understand much of what they're supposed to be learning. No wonder they become disaffected.

Of course, some teenagers will be disaffected even if we inject actual content into the elementary school curriculum— In the short-term, the only way we might be able to tell is to offer motivated students intensive tutoring in the subjects they're supposed to be learning— For the longer term, we need to revamp the elementary school curriculum so that poor kids are acquiring the tools that will allow them to access high school level work. Only then will students and their families be able to make a genuine choice between a path that leads to college and one that leads in a different, but equally fulfilling and possibly even lucrative, direction.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Cross-posted at DC Eduphile.

Smart Growth

- Can we develop communities for the people who already live in them?

- How strict land-use rules keep poor people in Mississippi

- Some Silver Spring residents want a park instead of affordable housing

Transit

- Why can't Metro change how it runs escalators, what info its signs display, or how easy it is to walk on station stairs?

- Did you know that Ballston used to be the last stop on the Orange Line?

- Recently-released federal reports shed light on Metro's ongoing problems

Education

- What do parents want? A good school, not too far, and some other kids that look like them

Public Space

- Add a piano to make your city square sing

- This square in Philadelphia is everything DC's Franklin Square could be

- NoMa's first underpass park is almost here!

Safe Streets

- Whether you're traveling from Virginia or Maryland, Capital Bikeshare isn't just for short trips

- Does the US highway system have high cholesterol?

- Copenhagen uses this one trick to make room for bikeways on nearly every street

Historic Preservation

- There are tunnels under Capitol Hill. Here's how they got there.

- National Harbor's colossal never-built skyscraper

- F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald are buried just a block away from the Rockville Metro station

Government

- In DC, access to medical care really depends on where you live

- Advisory Neighborhood Commissions, explained

- DC will have 300 hyper-local elections this fall. Can you help us sort through the candidates?

Education in DC

Answer Sheet

Class Struggle

DC Action for Children

DC Charter Schools Examiner

National

Bridging Differences

Diane Ravitch

Education Gadfly

Eduwonk

Hechinger Report

HuffPost Education

Larry Cuban

Of, By, For

Rick Hess Straight Up

Sara Mead's Policy Notebook

Shanker Blog

By or For Teachers

@the Chalk Face

Classroom Q&A;

Charting My Own Course

Coach G\s Teaching Tips

Curriculum Matters

Living in Dialogue

Teach for Us

Parents

Great Schools

K-12 Parents and the Public

ParentNet Unplugged

School Family

Technology in Education

Digital Education

Ed Tech Researcher

Other Regions

Chalkbeat Tennessee

Chalkbeat Indiana

EdNews Colorado

Gotham Schools (NY)